Prevent

Conflict evolved at a rapid pace in 2024, creating both opportunities and heightened risks for the protection of civilians. CIVIC monitors and documents new trends in warfare with a particular focus on four thematic areas: the deployment of artificial intelligence (AI) in the military domain, weaponized information, the climate-protection nexus, and private military and security companies (PSMCs). This section provides an overview of key developments in 2024 and their impact on civilians, efforts to improve protection through regulation or other initiatives, and ways forward for key actors.

AI is playing an increasingly prominent role on modern battlefields, leading to civilian harm and complicating oversight and accountability. In 2024, the use of so-called AI decision support systems (DSS) came under particular scrutiny, with Israel accused of relying too heavily on automated targeting to make decisions about deadly strikes, with minimal human oversight. While proponents of AI DSS claim its partially automated targeting will ultimately better protect civilians in conflict, human rights groups and others have raised strong concerns about inevitable errors and bias in targeting due to still-flawed and opaque AI systems. At the same time, massive investment in AI technology for military purposes continued globally in 2024, driven largely by the US and China. Several Big Tech firms scrapped policies that had previously banned the use of their technology by the defense industry.

Both state and non-state armed actors also increasingly relied on unpiloted aerial vehicles (UAVs), better known as drones, some of which are already incorporating AI technology. The use of smaller, first-person view (FPV) drones, in particular, has escalated rapidly in recent years. Armed actors have used these to target civilians directly, drop antipersonnel mines in crowded urban areas, or to attack humanitarian personnel, exposing civilians to new harms. International actors built on several initiatives to better regulate AI in 2024, with the Secretary General renewing his call for states to agree on an international legally binding treaty on lethal autonomous weapons (LAWS), or “killer robots,” by 2026.

While PMSCs have long been a feature of war, their deployment in conflicts has increased over the past decade. In 2024, the Russian Wagner Group and its proxies were accused of a wide range of abuses, primarily in the African Sahel region, including extrajudicial killings and enforced disappearances. A small subset of PMSCs have effectively evolved into tools of state power, occupying a legal gray area that further complicates regulation and accountability for abuses. In response, efforts to strengthen international frameworks for monitoring and oversight of PMSCs advanced incrementally in 2024, with states debating the draft text of a new international treaty at the UN.

The risks to civilians in conflict from weaponized information, including misinformation, disinformation, malinformation, and hate speech (MDMH), have escalated as new technology allows combatants and proxy actors to deploy information operations at unprecedented speed and scale. Such operations sometimes directly violate IHL, including by inciting violence against particular groups through hate speech, spreading terror through mass disinformation, or endangering civilians by manipulating population movements. Both states and NSAGs were accused of using MDMH in ways that could jeopardize civilians in 2024, notably in Israel, Ukraine, and Somalia. Aid actors are also often targeted through mis- and disinformation, endangering beneficiaries and staff and threatening access to humanitarian aid in some of the world’s most fragile contexts. In 2024, both civil society groups and the UN tried to put in place systems to better expose and counter such disinformation campaigns targeting humanitarians. With AI technology becoming increasingly accessible, there are growing concerns about the use of AI-generated synthetic content to fuel tensions or violence in conflict zones. While such AI-generated content appeared to be relatively limited in conflict contexts in 2024, new research warned this would likely change in the coming years, heightening risks for peace negotiations.

Climate change is compounding crises worldwide, increasing protection risks for already vulnerable populations. Civilians are facing the dual threat of climate-induced disasters and armed conflict in a growing number of countries, including in the DRC, Sudan, Syria, Somalia, and Yemen. In Sudan, famine triggered by both conflict and climate factors was confirmed in at least five areas in 2024, compounding protection risks amid a conflict increasingly characterized by atrocity crimes. By the end of last year, climate-induced internal displacement also reached record-breaking levels, affecting over 9.8 million people worldwide. In a positive development, there were growing signs of peacekeeping actors integrating climate risks into protection mandates, with UNMISS in South Sudan a leading example.

The Algorithms of Conflict: Military Use of AI and Civilian Harm

In 2024, armed actors increasingly deployed targeting and weapons systems using some form of AI across global conflict theaters, most notably in Ukraine. Both Russian and Ukrainian forces have long made use of UAVs for reconnaissance missions, providing real-time data and imagery through AI-powered cameras. Last year, Ukrainian forces also reportedly relied on drones with AI technology to avoid detection or jamming during strikes on energy infrastructure deep inside Russian territory.1 The proliferation of drone use in conflict settings continued to provoke civilian harm and intensified calls for greater accountability and oversight (see Spotlight: Proliferation of drones in warfare).

The use of AI-powered decision support systems (AI DSS) also came under heightened scrutiny in 2024, driven largely by developments in Israel. Media reporting highlighted how Israel allegedly used the AI DSS “Lavender” to identify and carry out strikes on suspected fighters from Hamas or other armed groups in Gaza, with minimal human oversight. Former operatives alleged that “Lavender” had been used to identify as many as 37,000 suspected fighters in the early phases of the conflict, with human analysts spending “less than 20 seconds” evaluating each AI-identified target before strikes.2 In addition, Israel relies on at least one other AI targeting system, “The Gospel,” to identify buildings and infrastructure affiliated with Hamas.3 The Israeli Defense Forces did not respond to many of the specifics raised in reporting on Lavender, but stated that AI programs are “merely tools” to support intelligence analysts and are not used for autonomous identification.4 Ukrainian forces have reportedly made use of AI in targeting against Russia as well, although primarily in a supportive and information role.5

While proponents claim that the greater precision of AI DSS will ultimately strengthen the protection of civilians, human rights groups and legal analysts have raised a number of concerns about their use, particularly regarding the high likelihood of mistakes and bias in target identification.6 The ICRC has long stressed that human judgment should be preserved in wartime decision making to ensure compliance with IHL, and in 2024 it emphasized the need to develop additional, specific measures to govern AI DSS, as well as technical solutions to improve data used in training such systems.7

In what analysts have called an “AI military gold rush,” investment in AI technology for defense purposes continued to escalate last year, largely driven by China and the US.8 Despite the US imposing sanctions on China’s AI sector in late 2024, Beijing continued to invest heavily in military AI and remained the top global exporter of military drones.9 In the US, there were signs of a new political defense economy emerging, with Pentagon investments increasingly flowing away from traditional defense contractors toward Silicon Valley.10 In 2024, for example, the US Army invested $480 million in Palantir software to simplify and organize battlefield information, while the Coast Guard awarded Shield AI a $198 million drone surveillance contract.11 Furthermore, approximately $130 billion of venture capital funds was invested in US defense start-ups between 2021 and 2024, according to one estimate.12 In a sign of this growing closeness between the AI and defense industries, both OpenAI and Meta updated their usage policies in 2024 to remove language banning the military use of their technologies.13 In December, OpenAI announced a partnership with defense company Anduril Industries to develop drone detection technology, referred to as counter-unpiloted aircraft systems (CUAS).14

Although efforts to govern and regulate the military use of AI made some headway in 2024, international bodies struggled to keep up with the breakneck pace at which technology was being developed and deployed. At the UN level, the Secretary-General in September 2024 presented a report on lethal autonomous weapons systems (LAWS) and renewed his calls for Member States to conclude a legally binding international treaty on LAWS by 2026 (for further details, see Spotlight: Proliferation of drones in warfare).15 Civil society groups have long campaigned for such a “killer robots” treaty and welcomed the report, while stressing the urgency of concluding a treaty that has already been under discussion for more than a decade.16 The UNGA furthermore passed its first-ever resolution (79/239) on AI in the military domain in December, affirming that international law applies to “all stages of the lifecycle” of AI.17 Following the resolution, the Secretary-General invited Member States and other actors to submit views on AI in the military domain “with specific focus on areas other than [LAWS].” This reflects growing concern that efforts to govern AI in conflict have so far been too narrowly focused on LAWS, disregarding the many other ways AI has the potential to shape almost every aspect of warfare.18 Furthermore, at the UN-led Summit of the Future in September, Member States agreed to establish, through the UN, a Global Dialogue on AI Governance, including its use in conflict.19

The European Union (EU) passed the AI Act in July, the first-ever comprehensive legal framework on AI worldwide.20 While human rights groups cautiously welcomed aspects of the Act, they raised concerns about the explicit exclusion of AI systems for “military, defence or national security purposes” to preserve the sovereignty of EU Member States in national defense policies.21 This omission has raised questions about how the Act applies to dual-use AI technologies.22 In September, South Korea hosted the second annual Responsible AI in the Military Domain (REAIM) Summit, which concluded with 61 states signing a “Blueprint for Action” to establish norms for AI use in the military domain.23

To protect civilians amid the growth in AI-powered warfare, it is crucial that states implement appropriate safeguards to mitigate risks of semi-autonomous weapons systems. This should include maintaining a high level of civilian oversight over all targeting decisions in conflict and ensuring that the IHL principles of proportionality, distinction, and precaution are at the core of all decision-making to minimize civilian harm. At the same time, states should closely monitor the increasing use of such technology in conflicts and carry out transparent investigations that meet international standards for reporting violations, while holding those responsible to account. Companies that develop AI technology for military use must furthermore adhere to the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, putting in place safeguards to ensure such technology is not used to cause undue civilian harm in conflict. Lastly, CIVIC urges states to heed the Secretary-General’s call to negotiate a legally binding instrument to regulate LAWS, ensuring their use complies with IHL.

Eyes in the Sky: How Drones are Redefining Warfare

In recent years, modern battlefields have increasingly been dominated by the use of unpiloted aerial vehicles (UAVs), more commonly known as drones. While the conflict in Ukraine since Russia’s 2022 full-scale invasion has become the primary example of the new “drone era” of warfare, their use has proliferated across other contexts—including Mali, Myanmar, Yemen, Somalia, Syria, and the oPT. Notably, drones are also no longer the exclusive purview of nation-states. They were embraced by a growing number of non-state armed groups (NSAGs) in 2024, not least due to their accessibility, low cost, and reach. The explosion in drone use has had enormous implications for the protection of civilians in conflicts, while also raising difficult questions about how international law and standards—including IHL—can and should be used to better regulate their use.

Drone usage has evolved considerably since the early 2000s, when primarily US strikes in countries including Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Somalia drew considerable media attention during the “War on Terror.” While earlier drone warfare relied mainly on large, expensive, and complex systems carrying heavy payloads used at long range—such as the “Predator” and “Reaper” models—the drones used in today’s conflicts are much more varied.24 The most significant development is the proliferation of smaller, first-person view (FPV) drones that can be used for reconnaissance, armed attacks (carrying explosive or incendiary weapons, or functioning as kamikaze weapons), or other military purposes. The most common FPV drones are commercial rotor or quadcopter drones manufactured by companies such as the Chinese firm DJI and later adapted for military purposes.

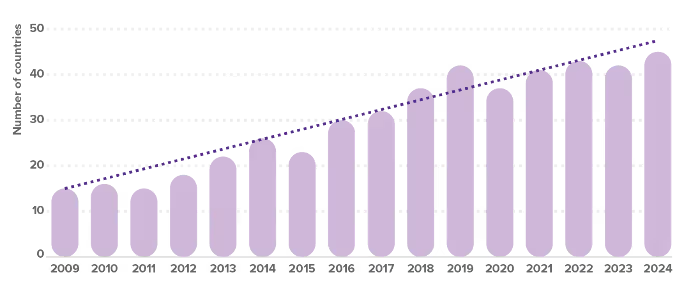

Usage data paints a stark picture of how drones have become a common feature in modern conflicts within the span of just a few years. In 2024, ACLED recorded at least 19,704 drone strikes across all conflicts it monitors, more than 15,000 of which took place in Russia or Ukraine. This marks an almost four-fold rise from the 4,525 strikes globally in 2023, and a staggering increase of more than 4,000 percent from the 447 strikes in 2020. In 2024, ACLED further recorded approximately 5,500 battle deaths (including both civilians and combatants) from drone strikes, representing a more than ten-fold increase from the death toll in 2020. At the same time, the number of actors using drones has also increased dramatically: while only three states were known to possess armed drones in 2010, that number had risen to 16 by 2018, and to 40 in 2023, the last year such figures were publicly available.25 NSAGs have adopted drones at an even greater pace, with the number of such groups carrying out at least one drone attack rising from six in 2018 to 91 in 2023 – an increase of more than 1,400 percent. It is equally telling that the number of companies globally manufacturing drones has increased from just six in 2022 to more than 200 in 2024.26

Drones have in many ways become the defining feature of the Russia-Ukraine conflict. Initially, both Russia and Ukraine relied mainly on larger, fixed-wing drones operating at longer range (such as the Turkish Bayraktar TB2 or the Iranian Shahed), carrying missiles to attack troops or infrastructure on the ground. Increasingly, however, smaller systems have come to dominate use—including some as small as the “Black Hornet,” with a wingspan of only 12 centimeters.27 Beyond aerial use, Ukraine has also seen the use of ground drones and marine drones to deliver supplies, evacuate wounded, or attack trenches. The latter include both surface vessels and submarine systems, which Ukraine has successfully used to target Russian patrol ships in the Black Sea, as well as helicopters.28

Drone use in Ukraine has escalated dramatically in the three years since Russia’s full-scale invasion began in 2022. Ukraine’s Ministry of Defense reported purchasing 1.5 million FPV drones in 2024 with plans to acquire many more in 2025, with a domestic production capacity of 4.5 million.29 An indication of the sheer number of drones used in the conflict is illustrated by the fact that Ukraine lost as many as 10,000 per day in 2024, according to the Royal United Services Institute (RUSI).30 RUSI also estimated that drones were responsible for as much as 70 percent of confirmed Russian losses.31 Russian forces have recently moved to seize the advantage in drone use, however, including by boosting domestic production and deploying more advanced drones with autonomous AI technology that are harder to intercept.32

Civilians in Ukraine have paid a heavy price for the proliferation of drone warfare. According to OHCHR, short-range FPV drones have emerged as a leading cause of civilian deaths and injuries in the conflict, even surpassing heavier weapons like missiles and artillery during certain periods. Civilian deaths from drone attacks in Ukraine rose from 23 in 2023 to 226 in 2024, with the vast majority attributed to Russian attacks in Ukrainian-controlled territory.33 Human Rights Watch has further documented how Russia used quadcopter drones to launch incendiary weapons and drop “petal” or “butterfly” anti-personnel mines in Ukrainian-controlled regions.34 In Kherson alone, at least 30 civilians were killed in such attacks during the latter half of 2024.35 Apart from deaths and injuries, these attacks have a broader impact on civilians by spreading terror and hindering access to food or basic services like healthcare, including through targeted attacks on hospitals and humanitarian actors.36

Beyond Ukraine, last year also saw drones gain prominence in other conflict theatres. In Myanmar, the military leadership largely managed to maintain its grip on power through air superiority, but from mid-2024 it increasingly shifted investment toward drone technology, which has long been used by NSAGs in the conflict. According to ACLED, Myanmar now ranks third in global drone use behind Ukraine and Russia.37 Rights groups have highlighted how both the military and ethnic armed groups have used drones to target civilians, including those belonging to the Rohingya minority group.38 In Yemen, the Houthis have been at the forefront of drone warfare in the conflict with Saudi Arabia, establishing Iranian-backed domestic drone production as early as 2017.39

In 2024, the Houthis increasingly relied on drones to enforce their partial blockade of maritime traffic in the Red Sea.40 In Sudan, both the armed forces and the RSF reportedly killed and injured unarmed civilians in drone attacks last year.41 Likewise, two Somali government airstrikes using Turkish-made drones on March 18 reportedly killed 23 civilians, including 14 children, in the Lower Shabelle region.42

The proliferation of drones in modern conflict theatres has sparked intense debate about the applicability of international law, including both IHL and human rights law. Earlier legal discourse primarily focused on the implications of long-range drone strikes against armed extremist groups and the associated risks to civilians through collateral damage, indiscriminate strikes, or flawed targeting criteria.43 The US, controversially, made use of “signature strikes” at the time, where all fighting-age men could be considered legitimate targets based on certain patterns of behavior or other indicators of suspected military activity. Human rights groups also raised questions about the lack of transparency surrounding such strikes, with major implications for accountability and victims’ access to remedies.44

More recent legal debate has shifted to the use of drones in open warfare, as well as challenges posed by the enormous growth of smaller FPV drones. This includes questions about when such drones, particularly commercial drones that have been modified, can be considered military objectives under IHL. There are also practical challenges related to their use as medical transports, partly because drones are often too small to display the Red Cross symbol or similar markings. Researchers have called for more coordinated action and dialogue on how to address the multiple issues arising from the explosion in consumer drone use in conflict.45

There is, however, broad agreement that drones should be guided by the legal requirements governing the use of force set out in international humanitarian law, as well as human rights law.46 In this sense, drones are not inherently unlawful or discriminatory weapons, but must be governed by the principles of proportionality, distinction, and precaution that also apply to other methods of warfare. As Human Rights Watch noted, their “lawful use depends on the operator, the technology used for targeting, and the payload”. While the increased precision of drones should, in theory, allow for greater mitigation of civilian harm, this has often not been the case in practice. In Ukraine, for example, Russia has been accused of violating IHL by deliberately targeting civilians with drones, using them to indiscriminately drop antipersonnel mines in densely populated areas, deliberately targeting hospitals and humanitarian actors with them, and more broadly using drones to spread terror among the population. Looking ahead, states are increasingly exploring how to better integrate AI into drone warfare, most prominently through AI-controlled drone “swarms” to overwhelm defenses.47

As noted above, efforts to regulate LAWS have gathered pace somewhat in recent years, including through calls for a legally binding international treaty. Commercial drone companies have also come under increasing scrutiny, with pressure for them to publicly respond to reports of their products being used in unlawful attacks and to restrict sales to actors found to have violated international human rights law. With significant challenges in monitoring current drone use, several countries are developing Remote ID standards to integrate drones into national air traffic control systems, although this remains a complex undertaking. While some commercial companies maintain logs or systems monitoring their drones, these are limited to showing only the location of drones and provide minimal insight into their intended use.48

To promote the protection of civilians in connection with the use of drones in conflict, governments and NSAGs should:

- Take all feasible precautions to avoid, or at the very least minimize, civilian casualties, including through stringent verification protocols to distinguish between civilians and military targets, and at all times respecting the IHL requirements of proportionality, distinction, and precaution.

- Ensure all drone operators receive thorough training in IHL, and IHRL as relevant, including the sanctions that apply for violations.

- Require all combatants using drones to maintain and publicize flight log so that oversight bodies within the military, government, or other institutions can carry out independent and transparent investigations into allegations of violations.

- Conduct regular and systematic assessments of drone use in conflict zones, and make these assessments available to the public and relevant oversight bodies.

- Work with commercial drone companies to develop and implement safeguards that prevent or minimize the unlawful use of drones in combat.

Blurred Lines: Accountability Gaps and the Spread of PMSCs in Conflict

While mercenaries as well as private military and security companies (PMSCs) are not new to conflict, their use has expanded across multiple contexts in recent years. PMSCs have often taken over functions traditionally associated with national armies, while their proliferation has been accompanied by widespread harms to civilians, including killings, torture, enforced disappearances, and CRSV.49 Accountability for such abuses has been rare, especially in fragile states where PMSCs are often employed by and fighting alongside national governments or other powerful actors. Some PMSCs have furthermore evolved into “covert tools of state power,” blurring the lines between private and state actors. These include Russia’s Wagner Group (see below), Türkiye’s SADAT, and outfits supported by the United Arab Emirates (UAE). Such groups often occupy a legal gray area that further complicates regulation and accountability.50 Since 2023, for example, the UAE’s alleged support for the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) in Sudan—including by providing mercenaries—has come under increasing scrutiny amid growing RSF-perpetrated atrocities.51

The Russian PMSC Wagner Group—which has been credibly accused of widespread human rights abuses in contexts including Libya, the CAR, Mali, and Ukraine—continued to expand operations in 2024.52 It did so, however, under new, restructured leadership that was reportedly more closely controlled by Moscow, following the mutiny and death of its former commander Yevgeny Prigozhin in 2023.53 In the Sahel region of West Africa (where the Wagner Group is now known as the Africa Corps), data from ACLED showed that political violence linked to Russian mercenaries spiked in early 2024, with the group deploying in Burkina Faso and Niger during the year, in addition to Mali and the CAR where it already had a presence.54 Reports of abuses have persisted. In Mali, the Wagner Group and state security forces summarily executed or forcibly disappeared dozens of people in 2024, according to Human Rights Watch.55 In the CAR, the UN accused Wagner-linked militia group Wagner Ti Azandé of carrying out widespread abuses, including grave violations against children.56

The increasing importance and changing nature of PMSCs in conflict zones have led to growing calls for stronger international regulation and oversight. The international standards regulating the use of PMSCs—such as the Montreux Document, the International Convention against the Recruitment, Use, Financing, and Training of Mercenaries and the International Code of Conduct (ICoC)—date from the 1990s and 2000s and are not legally binding.57 Member States of the UN Human Rights Council (HRC) have continued to highlight the human rights impacts of mercenaries, although efforts to strengthen international governance have made slow progress. In October, the UN HRC’s working group on mercenaries and human rights presented a report examining the growing role of mercenaries in the trafficking and proliferation of arms. The report stressed that mercenaries are often overlooked in the international arms control architecture, representing a significant regulatory gap, while the regulation that does exist often lacks compliance mechanisms or effective monitoring of such groups.58 Meanwhile, negotiations on a new international framework for the regulation, monitoring and oversight of PMSCs—under discussion since 2017—moved forward slowly, with a fourth draft text presented to States for feedback in July.59

To address the growing threat to civilians posed by PMSCs in conflict, CIVIC urges governments to support existing international initiatives to develop stronger regulatory and monitoring frameworks, including the international framework for the regulation, monitoring and oversight of PMSCs under development at the UN. In addition, it is crucial for states to set credible standards in national legislation for better monitoring and regulating PMSCs, which can be replicated and relied on as good practices at the international level. UN and civil society actors must also continue to play a crucial role in documenting abuses by PMSCs at the local level, particularly in fragile contexts where access is a challenge.

Weaponized Information

The spread of misinformation, disinformation, malinformation, and hate speech (MDMH) in conflict settings has shifted dramatically in the digital age, and is now carried out at unprecedented scale and speed.60 These forms of manipulated information have the potential to expose civilians, humanitarian actors, and others to a range of harms, sometimes in ways that directly violate IHL. Hate speech has, for example, been used to incite violence against certain groups, while disinformation has been utilized to spread fear and terror among civilian populations. Common tactics in such operations include deepfake videos, misleading mass information, and orchestrated hate campaigns. The plethora of misinformation in conflict – particularly when spread through social media channels - threatens to undermine trust in humanitarian actors, mainstream media, and state authorities.

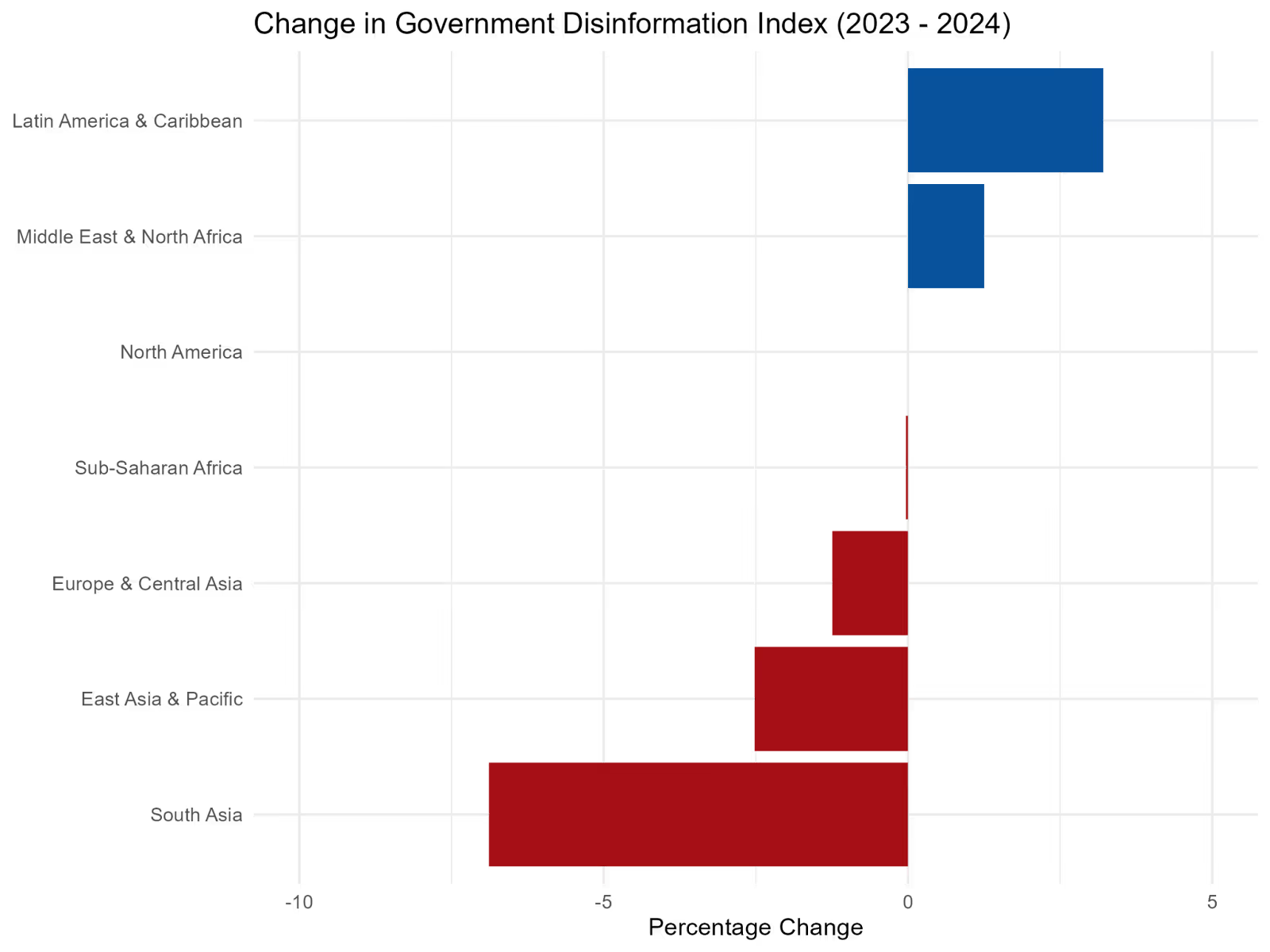

The worsening information environment in conflicts is reflected in CIVIC’s Civilian Protection Index, although this only tracks disinfomation spread by government actors, not non-state actors. The overall disinformation environment deteriorated globally by approximately one percent from 2023 to 2024, with an even sharper decline recorded over the past four years. The most notable national declines in 2024 were recorded in Bangladesh, Mongolia, and Moldova. South Asia, East Asia, and the Pacific experienced the largest regional declines overall, averaging four percent. In 2024, however, the disinformation environment improved in Latin America and the Caribbean, while data also showed a marginal improvement in the Middle East and North Africa.

Throughout 2024, actors deployed MDMH in a range of global conflicts, with the tools and tactics employed varying considerably between contexts. Human rights groups warned that the “unprecedented” spread of fake content, primarily through X (formerly Twitter), often far outpaced the content moderation efforts in place.61 While it is challenging to demonstrate a direct link between MDMH and civilian harm, there were several examples of such content becoming widespread in conflict contexts, muddying the information environment and threatening to inflame tensions. Israel’s Rafah offensive in May sparked a new wave of pro-Israeli online content falsely accusing Palestinians of using staged incidents to exaggerate civilian suffering in Gaza, with many users employing the denigrating term “Pallywood.”62 In Somalia, the government has struggled to counter mis- and disinformation spread by al-Shabaab, an NSAG, including claims that the country is under attack from “crusaders” and that the authorities were anti-Islamic. The government has ordered the shutdown of websites and social media accounts accused of spreading such content, but al-Shabaab is often able to quickly re-register accounts under new domains and usernames. According to one researcher, al-Shabaab is “the largest single producer of terrorist material on the internet.”63 In Ukraine, pro-Kremlin accounts were accused of spreading false evacuation orders to civilians in Kharkiv.64 CIVIC has previously reported on how such attempts to manipulate population movements can put civilians at direct risk of harm.65

Aid actors were often targeted with mis- and disinformation, endangering humanitarian staff, while potentially also undermining civilians’ access to humanitarian aid in some of the world’s most fragile contexts. In his Protection of Civilians Report, the UN Secretary-General warned of the particularly harmful effects of misinformation in eroding trust in humanitarian actors, highlighting how such campaigns undermined aid organizations in contexts as varied as Burkina Faso, the DRC, and the oPT.66 Disinformation campaigns in Syria, Ukraine, and Mali have also spread false information about healthcare systems or attacks on hospitals, potentially dissuading civilians from seeking medical care.67 In Sudan, at least one aid group was falsely accused of weapons smuggling.68

In response, humanitarian and peace actors are investing in efforts to counter the threats posed by MDMH. In Ethiopia, local civil society groups have successfully identified and petitioned for the removal of fake social media posts, including those targeting humanitarian aid groups.69 In June, the UN Department of Peace Operations (DPO) and the Office of the Special Adviser on the Prevention of Genocide launched a report on how to better distinguish between and counter hate speech, misinformation, and disinformation in conflict-affected areas. The report complements the work of a new, dedicated team to support peacekeeping missions with guidance and training on MDMH, established by DPO in 2023.70

Rapid advances in AI technology have raised concerns about the potential for AI-generated content to add to the already cluttered MDMH environment in conflict zones. The creation of so-called synthetic content has skyrocketed in recent years as tools to generate images or video from text became widely available. Already at the end of 2023, there were approximately 16 million hyper-realistic fake images online.71 During 2024, widespread state-sponsored generative AI content was used to disrupt elections, as more than two billion people went to the polls globally. Its spread in armed conflict appeared more limited.72 However, research from Witness found that while the use of generative AI techniques by malicious actors in conflict-affected countries was still relatively rare in 2024, this is likely to change in the next two-to-three years as adoption of such technology becomes more accessible. Some of the risks highlighted included increased personalized and automated propaganda, distortion of historical narratives, amplified gender-based violence online and offline, and heightened disinformation dynamics. Synthetic media could also undermine peace processes if enough distrust were created in shared information environments.73 In 2024, OpenAI also published its first-ever report on how its AI tools had been used in information operations. While the company found that malicious actors had relied on its tools in the context of conflict in Ukraine, Israel, and Iran, it stated that none of the campaigns had gained enough traction to reach large audiences.74

Russia has, however, been credibly accused of relying on AI to manage and create content from bot farms to spread pro-Kremlin propaganda, in particular in the context of the conflict in Ukraine.75 At the same time, both Russia and Ukraine have used AI-generated content in apparent attempts to spread misinformation and panic, primarily through “deepfake” videos of political or military leaders making false claims about conscription drives or the surrender of their own forces.76 Some researchers have warned that such propaganda content could ultimately filter into and “contaminate” output from widely used large-language models such as ChatGPT, Grok, or Copilot.77

Despite the rapidly growing threat of MDMH to civilians in conflict, efforts to counteract and legislate it are challenging at both the international and national levels. There is a need to ensure that legislation does not place undue restrictions on the right to freedom of expression and is not misused by authoritarian actors. Accountability and countermeasures are also complicated by the reality that perpetrators are often anonymous or private actors, as well as by the scale and speed of modern disinformation campaigns. Despite these challenges, international and regional organizations introduced in recent years a number of initiatives to better highlight or govern harmful information operations in conflict. In April 2024, the HRC passed a resolution on MDMH, emphasizing the particular threat of disinformation campaigns aggravating violence or suffering in conflict, while commissioning a broader report on the impact of disinformation on the enjoyment and realization of human rights.78 In another UN-led initiative, the Pact for the Future and its annexed Global Digital Compact contains several non-binding commitments on MDMH, including to prioritize clear and accurate information flows in crisis situations.79 At a regional level, the European Union’s AI Act, which came into effect in August, included provisions to combat MDMH such as transparency measures that clearly label synthetic content and requirements to strengthen detection systems, further complementing the EU Digital Services Act that was enacted in 2023.80

To counter the growing threat of MDMH in conflict, states should:

- Implement strong national legislation requiring technology companies to better regulate the spread of MDMH, following the example set by the EU through the Digital Services Act.

- Engage in international cooperation on best practices to counter MDMH campaigns and develop joint counter-efforts, without imposing undue restrictions on the right to freedom of expression.

- Address the growing threat of AI-generated MDMH by investing in the development of independently audited detection technologies accompanied by human fact-checking, while putting in place strong safeguards to prevent their misuse that could unduly restrict the right to freedom of expression.

- Invest in broader AI and MDMH literacy campaigns for the general public and foster international coordination in the adoption of best practices.

The Multiplier Threat of Climate Change and Conflict

Climate change is increasingly compounding the negative effects of conflicts worldwide, driving new risks for civilians and deepening existing vulnerabilities. Climate shocks can weaken resilience and overwhelm adaptation mechanisms. Slow onset hazards—such as sea-level rise and desertification—can also increase risks of violence by fueling displacement or competition for resources. Climate events in conflict-affected regions can exacerbate food and water insecurity, damage health systems, and weaken infrastructure already disrupted by conflict. The DRC, Sudan, Syria, Somalia, and Yemen are among the countries most severely affected by both severe climate-related hazards and conflict.81 In Sudan, famine—at least partly climate-induced and worsened by ongoing conflict—was confirmed in five areas in 2024, including Zamzam camp in North Darfur.82

Women and girls are often driven into gendered high-risk coping strategies for resource collection as a result of increasing vulnerabilities from climate and conflict-induced risks. This often involves traveling longer distances to gather water or fuel because of environmental degradation, which increases vulnerability to conflict-related sexual violence. In Ethiopia, for example, almost half of all refugee women surveyed in 2024 by UNHCR reported sexual violence while traveling long distances to collect firewood.83

Climate-related disasters in conflict-affected countries also increase the strain on states’ protection capacities, leaving governments overstretched by overlapping crises. Already scarce emergency resources are often committed to security operations, reducing funds available to address civilian needs arising from climate hazards. Damage to critical infrastructure also creates severe humanitarian access challenges. This was the case in South Sudan, where flooding cut off 15 main roads and submerged 58 health facilities in October alone, complicating access to healthcare for civilians in conflict-prone regions.84

By the end of 2024, both conflict- and climate-driven internal displacement had reached record-breaking levels globally, as conflicts and violence left 73.5 million displaced, while disasters displaced an additional 9.8 million.85 In practice, however, people forced to flee their homes increasingly face the dual threat of both conflict and climate change (See Spotlight: When Guns, Disasters, and Displacement Meet).

When Guns, Disaster, and Displacement Meet

This article was authored by the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC)

In many countries, the impacts of both conflict- and disaster-induced displacement are increasingly intertwined, making crises more complex and prolonging the plight of those forced to flee their homes. All but four of the 49 countries and territories where conflict displacements were identified in 2024 also recorded disaster displacements. The number of countries reporting both types of displacement has tripled since 2009.86

The increase is, in part, the result of greater data availability, but it also reflects a clear trend. Some of the world’s largest and most protracted conflict-displacement situations are increasingly affected by disasters such as floods and storms, and this combination further erodes the resilience of displaced persons.

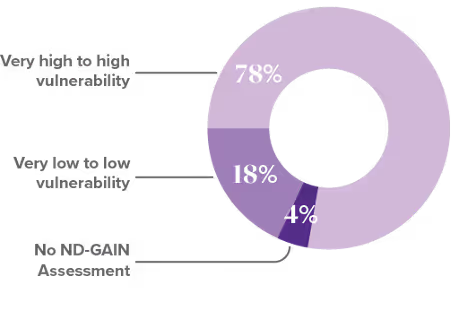

An analysis of data from IDMC and the Notre Dame Global Adaptation Initiative (ND-GAIN), which assesses countries' vulnerability to and ability to adapt to climate change, reveals that more than three-quarters of people internally displaced by conflict and violence at the end of 2024 were living in countries with high or very high vulnerability to climate change.87

This intersection of climate and conflict risks undermined protection for displaced persons in a number of countries in 2024. In the DRC, above-average rainfall triggered flood displacements in the eastern provinces, which have long been affected by conflict. Roads between major urban areas were inundated or blockaded by non-state armed groups, cutting the delivery of much-needed aid to hundreds of thousands of IDPs. This aggravated sanitary conditions and increased waterborne diseases, while reducing agricultural production and heightening food insecurity.88

Yemen reported its highest number of disaster displacements on record in 2024. Most took place in Al Hodeidah, Hajjah, and Ma’rib governorates, which are home to nearly half of the country’s 4.8 million IDPs, forcing some to flee again. The floods also moved landmines and unexploded ordnance, increasing the number of casualties and injuries from these devices and hampering the delivery of aid to displaced persons.89 In Mozambique and Myanmar, cyclones Chido and Yagi hit populations already uprooted by conflict and violence, prolonging their displacement and delaying their recovery. From Afghanistan to the Philippines and from South Sudan to Syria, the overlapping impacts of conflict and disasters continue to undermine IDPs’ prospects of finding durable solutions to their displacement.90

Disasters are likely to continue triggering repeated displacement, extending or amplifying the vulnerabilities displaced persons experience, and undermining durable solutions and sustainable development efforts. This means that governments, aid actors, donors, and others must increasingly prioritize building disaster resilience in fragile and conflict-affected countries.

Zooming In: Risks and Policy Solutions in Nigeria

The intersection of conflict, weather-related disasters, and displacement is starkly illustrated in Nigeria’s north-eastern Borno state. Conflict and disasters triggered new and repeated displacement in the country in 2024. Nigeria was home to 3.7 million IDPs at the end of the year, among the highest figures in sub-Saharan Africa. Nearly half of the displaced persons were living in Borno state, which has experienced conflict and violence since 2009.

Severe floods triggered 121,000 movements across Borno in 2024, some of which affected people already uprooted by conflict and violence, setting back their recovery as well as the government's ongoing durable solutions efforts (see below).91 About half of the displacement occurred in the state capital of Maiduguri after heavy rains and structural damage caused the Alau dam to overflow in September, inundating about 40 percent of the city.92 Some displacement camps were cut off for days, while new arrivals surged in others, which led to overcrowding, a rise in food insecurity, and water and sanitation issues.93

The floods took place against the backdrop of a government-led initiative to close all displacement camps in Borno by the end of 2024.94 Seventeen had been closed by June but some had to be reopened to host people fleeing the floods.95

Even after the floodwaters receded, some IDPs remained in the camps because they were struggling to recover their livelihoods, particularly those who had relied on agriculture and informal work. Others cited insecurity as a barrier to accessing markets in their areas of origin.96 Additionally, a rise in housing, land, and property disputes was reported following the June floods, including forced evictions and communal conflicts.97

The number of displacements triggered by conflict and violence in Borno has fallen significantly over the past decade, but around 40,000 movements were still reported in 2024. Many occurred in areas already hosting displaced people, some of whom were subjected to violence and kidnapping.98 Shelter conditions were also inadequate, putting people at risk of secondary movement as a result of floods.99 These events illustrate how the overlapping impacts of conflict and disasters can impede progress toward resolving displacement.

To tackle these challenges, the state government developed the Borno State Strategy for Durable Solutions to Internal Displacement 2025-2027, which outlines key priorities and interventions to address the short and long-term needs of IDPs and host communities.100 The strategy, which is aligned with the 2021 National Policy on Internally Displaced Persons, covers sustainable returns, disaster management, and economic development, and includes plans to expand Maiduguri’s housing and public infrastructure to facilitate local integration.101 It also acknowledges the need to tackle the underlying causes of conflict through education, economic opportunities, and transitional justice programs.102

Similar initiatives were undertaken in neighboring Adamawa and Yobe states, which produced action plans on solutions to internal displacement in 2024.103 The plans, which are in line with international standards and the Kampala Convention, are intended to facilitate IDPs’ safe return and reintegration by harnessing development investments.104 At the federal level, the National Commission for Refugees, Migrants, and IDPs is also developing a National Action Plan and a Standard Operating Procedure on Durable Solutions.

These policies and initiatives represent an essential first step in resolving one of Africa’s largest and most protracted internal displacement situations, and they reflect the federal and state governments’ leadership and political will to do so. Humanitarian and development actors can play a vital role in ensuring these initiatives’ success, including by closely monitoring progress and producing solid evidence on how weather-related disasters and conflict are interlinked with displacement to ensure solutions consider both root causes and their interaction.

New research is increasingly also exposing how climate and conflict are mutually reinforcing. In Ukraine, for example, Russia’s destruction of chemical plants and natural ecosystems has led to environmental degradation, undermining climate mitigation and adaptation.105 In Gaza, one recent study concluded that greenhouse gas emissions during the first 120 days of the conflict surpassed the annual output of 26 individual countries—including emissions from fighter jets, cargo flight fuel, bombing raids, and artillery production, among other war-related activities.106 Resource scarcity from climate disasters can also lead to the politicization of relief distribution, with harsh consequences for civilians. In Somalia, for example, the 2020-2023 drought has influenced conflict dynamics, as al-Shabaab reportedly leverages water access for political ends.107

In a positive development, there are emerging signs that peacekeeping actors are adapting civilian protection mandates to include climate risks. A leading example is the UN Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS). In 2024, CIVIC documented how the UNSC expanded UNMISS’s mandate to explicitly integrate climate-related threats into POC efforts.108 UNMISS has responded by using climate indicators in threat assessments, deploying a Climate Security Advisor, and fortifying its Early Warning and Rapid Response systems. This reflects a growing realization that climate change in South Sudan—the world’s second most vulnerable country to natural hazards—is inseparable from civilian safety.109 At the same time, UNMISS must navigate the challenge of balancing climate-related tasks with its POC focus and leverage its influence to connect actors across the humanitarian-development-peace nexus. A key lesson from South Sudan is the importance of balancing specific and flexible language on climate change and POC in peacekeeping mandates to allow local actors to tailor interventions to field-level realities.

Another key challenge is acute climate-funding shortages in the countries that need it the most. Conflict-affected countries receive notably less adaptation funding per capita than other low-income countries—just $2.1 per person annually in extremely fragile states, according to UNHCR.110 Global humanitarian leaders have called for a dramatic increase in climate financing for conflict-affected countries, and for such funding to prioritize local actors in line with Grand Bargain commitments.111 During COP29, the G7+ (a group representing over 300 million people in conflict and fragility affected states) called for $20 billion per year in adaptation finance to such states by 2026.112

To meet this mounting challenge, decisive shifts are needed by governments, donors, aid actors, and development actors. They should:

- Prioritize multi-sectoral collaboration across state actors, non-governmental organizations, civil society, and civilian communities in contexts affected by dual climate-conflict crises.

- Center the vulnerability of specific groups in protection efforts to address the distinct risks faced by women, children, the elderly, and people with disabilities in protection strategies during and after climate-driven crises.

- Ensure that security forces are trained and equipped to manage climate-related threats without compromising civilian safety, with robust accountability and monitoring mechanisms in place.

- Safeguard and increase climate financing in conflict-affected settings, in close coordination with development and protection actors.

- Invest in climate-related resilience at the local level in conflict contexts, including by resourcing and prioritizing holistic interventions, education, sustainable livelihoods, and climate-resilient infrastructure.

Footnotes

- Vasco Cotovio, Clare Sebastian, and Allegra Goodwin, “Ukraine’s AI-enabled drones are trying to disrupt Russia’s energy industry. So far, it’s working,” CNN, April 2, 2024, https://edition.cnn.com/2024/04/01/energy/ukrainian-drones-disrupting-russian-energy-industry-intl-cmd/index.html

- Yuval Abraham, “‘Lavender’: The AI machine directing Israel’s bombing spree in Gaza,” +972 Magazine, April 3, 2024, https://www.972mag.com/lavender-ai-israeli-army-gaza/; Bethan McKernan and Harry Davies, “‘The machine did it coldly’: Israel used AI to identify 37,000 Hamas targets,” The Guardian, April 3, 2024, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2024/apr/03/israel-gaza-ai-database-hamas-airstrikes

- Harry Davies, Bethan McKernan, and Dan Sabbagh, “‘The Gospel’: how Israel uses AI to select bombing targets in Gaza,” The Guardian, December 1, 2023, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/dec/01/the-gospel-how-israel-uses-ai-to-select-bombing-targets

- “The IDF's Use of Data Technologies in Intelligence Processing,” IDF, June 18, 2024, https://www.idf.il/210062.

- Yasmeen Serhan, “How Israel Uses AI in Gaza—And What It Might Mean for the Future of Warfare,” Time, December 18, 2024, https://time.com/7202584/gaza-ukraine-ai-warfare/

- Elke Schwarz, “The (im)possibility of responsible military AI governance,” ICRC Humanitarian Law and Policy Blog, December 12, 2024, https://blogs.icrc.org/law-and-policy/2024/12/12/the-im-possibility-of-responsible-military-ai-governance/

- ICRC and Geneva Academy, Expert Consultation Report on AI and Related Technologies in Military Decision-Making on the Use of Force in Armed Conflicts, March 2024.

- Raluca Csernatoni, “Governing Military AI Amid a Geopolitical Minefield,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, July 17, 2024, https://carnegieendowment.org/research/2024/07/governing-military-ai-amid-a-geopolitical-minefield?lang=en¢er=europe

- Akashdeep Arul, “How China is using AI for warfare,” Center for Security and Emerging Technology, February 21, 2022, https://cset.georgetown.edu/article/how-china-is-using-ai-for-warfare/

- Colin Demarest, “Tech race spurs U.S. investment in new defense suppliers,” Axios, July 17, 2024, https://www.axios.com/2024/07/17/military-defense-contractors-tech-ai-disrupters

- Colin Demarest, “Shield AI to let Hivemind software fly three more aircraft,” C4ISRNET, April 8, 2024, https://www.c4isrnet.com/artificial-intelligence/2024/04/08/shield-ai-to-let-hivemind-software-fly-three-more-aircraft/

- Margaux MacColl, “Palantir’s CTO, and 13th employee, has become a secret weapon for Valley defense tech startups,” TechCrunch, September 1, 2024, https://techcrunch.com/2024/09/01/palantirs-cto-and-13th-employee-has-become-a-secret-weapon-for-valley-defense-tech-startups/

- Sam Biddle, “OpenAI Quietly Deletes Ban on Using ChatGPT for ‘Military and Warfare,’” The Intercept, January 12, 2024, https://theintercept.com/2024/01/12/open-ai-military-ban-chatgpt/ Mike Isaac, “Meta Permits Its A.I. Models to Be Used for U.S. Military Purposes,” The New York Times, November 4, 2024, https://www.nytimes.com/2024/11/04/technology/meta-ai-military.html

- Mike Stone and Aishwarya Jain, “Defense firm Anduril partners with OpenAI to use AI in national security missions,” Reuters, December 4, 2024, https://www.reuters.com/technology/artificial-intelligence/defense-firm-anduril-partners-with-openai-use-ai-national-security-missions-2024-12-04/

- UN General Assembly, Report of the Secretary-General on lethal autonomous weapons systems, UN Doc. A/79/88, July 1, 2024.

- Isabelle Jones, “Next steps for treaty on killer robots laid out in UN Secretary-General report,” Stop Killer Robots, August 9, 2024, https://www.stopkillerrobots.org/news/next-steps-un-secretary-general-report/

- UN General Assembly, UN Doc. A/RES/79/239, December 31, 2024, para. 1.

- Raluca Csernatoni, “Governing Military AI Amid a Geopolitical Minefield.”

- UN General Assembly, Pact for the Future, UN Doc. A/RES/79/1, September 2024.

- European Union, “Regulation (EU) 2024/1689 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 June 2024 laying down harmonised rules on artificial intelligence,” Official Journal of the European Union, June 13, 2024, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32024R1689

- European Union, “Artificial Intelligence Act (Regulation (EU) 2024/1689) art. 2, para. 3,” Official Journal of the European Union, June 13, 2024, https://artificialintelligenceact.eu/article/2/

- Raluca Csernatoni, “Weaponizing Innovation? Mapping Artificial Intelligence-enabled Security and Defence in the EU,” EU Non-Proliferation and Disarmament Consortium, July 2023, https://www.sipri.org/publications/2023/eu-non-proliferation-and-disarmament-papers/weaponizing-innovation-mapping-artificial-intelligence-enabled-security-and-defence-eu

- Republic of Korea Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Outcome of Responsible AI in Military Domain (REAIM) Summit 2024, September 10, 2024.

- Sandra Krähenmann and George Dvaladze, “Humanitarian Concerns Raised by the Use of Armed Drones,” Geneva Call, June 16, 2020, https://www.genevacall.org/news/humanitarian-concerns-raised-by-the-use-of-armed-drones/.

- Michael Horowitz, Joshua A. Schwartz, and Matthew Fuhrmann, “Who’s prone to drone? A global time-series analysis of armed uninhabited aerial vehicle proliferation,” Conflict Management and Peace Science Conflict Management and Peace Science 39, no. 2 (November 2022).

- Rhordan Stephens, “How drones have shaped the nature of conflict,” Visions of Humanity, June 13, 2024, https://www.visionofhumanity.org/how-drones-have-shaped-the-nature-of-conflict/

- Ulrike Franke, “Drones in Ukraine and beyond: Everything you need to know,” European Council on Foreign Relations, August 11, 2023, https://ecfr.eu/article/drones-in-ukraine-and-beyond-everything-you-need-to-know

- Abdujalil Abdurasulov, “Ukraine war: The sea drones keeping Russia's warships at bay,” BBC, March 12, 2024, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-68528761 David Kirichenko, “Ukraine’s Marauding Sea Drones Bewilder Russia,” Center for European Policy Analysis, January 30, 2025, https://cepa.org/article/ukraines-marauding-sea-drones-bewilder-russia/

- “У 2025 році Міноборони планує закупити 4.5 млн FPV-дронів – Гліб Канєвський” [“In 2025, the Ministry of Defence plans to procure 4.5 million FPV drones – Hlib Kanievskyi”], Ministry of Defense of Ukraine, March 10, 2025, https://mod.gov.ua/news/u-2025-roczi-minoboroni-planuye-zakupiti-4-5-mln-fpv-droniv-glib-kanyevskij

- Jack Watling and Nick Reynolds, “Meatgrinder: Russian Tactics in the Second Year of Its Invasion of Ukraine,” RUSI, May 2023, https://www.rusi.org/explore-our-research/publications/special-resources/meatgrinder-russian-tactics-second-year-its-invasion-ukraine

- Mark Boris Andrijanič, “A Western-funded drone surge could end Russia’s invasion of Ukraine,” Atlantic Council, July 14, 2025, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/ukrainealert/a-western-funded-drone-surge-could-end-russias-invasion-of-ukraine/

- Ibid.

- “Deadly Drones: Civilians at Risk from Short-Range Drones in Frontline Areas of Ukraine, 24 February 2022—30 April 2025,” June 26, 2025, UN OHCHR, https://ukraine.ohchr.org/en/Deadly-drones-Civilians-at-risk-from-short-range-drones-in-frontline-areas-of-Ukraine-24-February-2022-30-April-2025

- Ukraine has also made use of such “flamethrower” drones in the conflict, but there is no indication that they have caused civilian harm. See, for example, Brad Lendon, Isaac Yee, and Kosta Gak, “Ukraine’s ‘dragon drones’ rain molten metal on Russian positions in latest terrifying battlefield innovation,” CCN, September 7, 2024, https://edition.cnn.com/2024/09/07/europe/ukraine-thermite-dragon-drones-intl-hnk-ml

- Human Rights Watch, Hunted From Above: Russia’s Use of Drones to Attack Civilians in Kherson, Ukraine, June 3, 2025.

- “Deadly Drones: Civilians at Risk from Short-Range Drones in Frontline Areas of Ukraine, 24 February 2022—30 April 2025,” UN OHCHR.

- Su Mon, “The war from the sky: How drone warfare is shaping the conflict in Myanmar,” ACLED, July 1, 2025, https://acleddata.com/report/war-sky-how-drone-warfare-shaping-conflict-myanmar

- Vibhu Mishra, “UN officials alarmed by civilian targeting amid renewed fighting in Myanmar,” UN News, July 29, 2024, https://news.un.org/en/story/2024/07/1152591 Amnesty International, “Myanmar 2024,” 2024, https://www.amnesty.org/en/location/asia-and-the-pacific/south-east-asia-and-the-pacific/myanmar/report-myanmar/

- Conflict Armament Research, Evolution of UAVs Employed by Houthi Forces in Yemen, February 2020.

- Luca Nevola and Valentin d’Hauthuille, “Six Houthi drone warfare strategies: How innovation is shifting the regional balance of power,” ACLED, August 6, 2024, https://acleddata.com/report/six-houthi-drone-warfare-strategies-how-innovation-shifting-regional-balance-power

- “Fanning the Flames: Sudanese Warring Parties’ Access To New Foreign-Made Weapons and Equipment,” Human Rights Watch, September 9, 2024, https://www.hrw.org/news/2024/09/09/fanning-flames#_Toc176538070; “Drone warfare reaches deeper into Sudan as peace talks stall,” ACLED, August 23, 2024, https://acleddata.com/report/drone-warfare-reaches-deeper-sudan-peace-talks-stall-august-2024

- “Somalia: Death of 23 civilians in military strikes with Turkish drones may amount to war crimes – new investigation”, Amnesty International, May 7, 2024, https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2024/05/somalia-death-of-23-civilians-in-military-strikes-with-turkish-drones-may-amount-to-war-crimes-new-investigation/

- Emily Crawford, “The Principle of Distinction and Remote Warfare,” in Research Handbook on Remote Warfare, ed. Jens David Ohlin (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing, 2017).

- Sandra Krähenmann and George Dvaladze, “Humanitarian Concerns raised by the Use of Armed Drones,” Geneva Call, June 16, 2020, https://www.genevacall.org/news/humanitarian-concerns-raised-by-the-use-of-armed-drones/ Amnesty International USA, “Amnesty International USA Statement for the Record for February 9th hearing on “‘Targeted Killing’ and the Rule of Law: The Legal and Human Costs of 20 Years of U.S. Drone Strikes,”” February 9, 2022, https://www.amnestyusa.org/blog/targeted-killing-and-the-rule-of-law/

- Faine Greenwood, “Consumer drones in conflict: where do they fit into IHL?” ICRC Humanitarian Law and Policy Blog, March 15, 2022, https://blogs.icrc.org/law-and-policy/2022/03/15/consumer-drones-conflict-ihl/

- UN Human Rights Council, Report of the Special Rapporteur on extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary executions, Christof Heyns, UN Doc. A/HRC/26/36, April 1, 2014.

- Frank Bajak, “US-China competition to field military drone swarms could fuel global arms race,” AP News, April 12, 2024, https://apnews.com/article/us-china-drone-swarm-development-arms-race-e5808a715415d709f466da00cdeab10f

- Faine Greenwood, “Consumer drones in conflict: where do they fit into IHL?” ICRC Humanitarian Law and Policy Blog, March 15, 2022, https://blogs.icrc.org/law-and-policy/2022/03/15/consumer-drones-conflict-ihl/.

- See, for example, CIVIC and DCAF, The growing use of private military and security companies in conflict settings: How to reduce threats to civilians?, August 4, 2022.

- Robin van der Lugt, “The 1%: Doing Business With Proxy Military Companies,” Geneva Academy of International Humanitarian Law, December 2024, https://www.geneva-academy.ch/joomlatools-files/docman-files/The%201%20Percent%20Doing%20Business%20with%20Proxy%20Military%20Companies.pdf

- “UAE Complicit in Sudan Slaughter,” CIVICUS, July 4, 2024, https://lens.civicus.org/uae-complicit-in-sudan-slaughter/ “Sudan military destroyed UAE plane carrying Colombian mercenaries: State TV,” Aljazeera, August 7, 2025, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2025/8/7/sudan-says-army-destroyed-uae-aircraft-killing-40-colombian-mercenaries

- Raphael Parens, Colin P. Clarke, Christopher Faulkner, and Kendal Wolf, “The Wagner Group’s Expanding Global Footprint,” Foreign Policy Research Institute, April 2023, https://www.fpri.org/article/2023/04/the-wagner-groups-expanding-global-footprint

- Danish Institute for International Studies, The rise and fall of the Wagner Group, 2025; Erin Banco, “Thousands of former Wagner fighters are now answering to Moscow,” POLITICO, April 28, 2024, https://www.politico.com/news/2024/04/28/wagner-fighters-russia-africa-00154595

- Ladd Serwat and Héni Nsaibia, “Q&A: The Wagner Group’s new life after the death of Yevgeny Prigozhin,” ACLED, August 21, 2024, https://acleddata.com/brief/qa-wagner-groups-new-life-after-death-yevgeny-prigozhin

- “Mali: Army, Wagner Group Disappear, Execute Fulani Civilians,” Human Rights Watch, July 22, 2025, https://www.hrw.org/news/2025/07/22/mali-army-wagner-group-disappear-execute-fulani-civilians

- OHCHR, Rapport public sur les violations et atteintes graves aux droits de l’homme commises par les Wagner Ti Azandé et les Azandé ani KPI Gbé du 1 au 7 octobre 2024 à Dembia et Rafaï, préfecture du Mbomou, March 4, 2025.

- Jelena Aparac, Gabor Rona and Shaista Shameem, “Regulating Private Military and Security Companies: What’s in it for States?,” EJIL: Talk!, April 7, 2025, https://www.ejiltalk.org/regulating-private-military-and-security-companies-whats-in-it-for-states/

- UN Working Group on Mercenaries, Role of mercenaries, mercenary-related actors and private military and security companies in the trafficking and proliferation of arms, UN Doc. A/HRC/57/45, September 9, 2024, para. 70.

- UN OHCHR, Revised fourth draft instrument on an international regulatory framework on the regulation, monitoring of and oversight over the activities of Private Military and Security Companies, March 5, 2025.

- Steven J. Barela, “Digital Disingformation Operations in Armed Conflict,” Geneva Academy of International Humanitarian Law, February 2025, https://www.geneva-academy.ch/joomlatools-files/docman-files/Digital%20disinformation%20operations%20in%20Armed%20Conflict%20(1).pdf

- “CSO warns that disinformation & hate speech on social media fuel war crimes against Gaza,” Business & Human Rights Resource Centre,October 13, 2023, https://www.business-humanrights.org/en/latest-news/cso-warns-that-disinformation-and-hate-speech-on-social-media-fuel-war-crimes-against-gaza

- Blair Simpson-Wise, “Rafah offensive sparks fresh wave of 'Pallywood' claims,” AAP News, May 23, 2024, https://www.aap.com.au/factcheck/rafah-offensive-sparks-fresh-wave-of-pallywood-claims/

- Harun Maruf, “Inside Somalia’s War on Al-Shabab Disinformation,” VOA News, March 14, 2024, https://www.voanews.com/a/inside-somalia-s-war-on-al-shabab-disinformation/7528211.html In December 2023, the UN Security Council furthermore passed resolution 2713 urging Member States to support the Somali government to better counter al-Shabaab’s MDMH online. UN Security Council, UN Doc. S/RES/2713(2023), December 1, 2023.

- Maria Avdeeva, "Bombs and disinformation: Russia’s campaign to depopulate Kharkiv", Atlantic Council, April 29, 2024. https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/ukrainealert/bombs-and-disinformation-russias-campaign-to-depopulate-kharkiv/

- CIVIC, Unprecedented Risks to Civilians from the Spread of Disinformation in Ukraine, November 8, 2023.

- UN Security Council, Report of the Secretary-General on protection of civilians in armed conflict, UN Doc. S/2025/271, May 15, 2025, para. 38.

- Gemma Bowsher, Richard Sullivan, and Filippa Lentzos, “Tackling health disinformation in conflict settings,” The Lancet 405, no. 10484 (March-April 2025).

- “False allegations endanger humanitarian workers in Sudan,” Norwegian Refugee Council, November 5, 2024, https://www.nrc.no/news/2024/november/false-allegations-endanger-humanitarian-workers-in-sudan/

- Simegnish Yekoye, “Fact-checkers in Ethiopia take on disinformation amid rising tensions,” VOA News, January 30, 2025, https://www.voanews.com/a/fact-checkers-in-ethiopia-take-on-disinformation-amid-rising-tensions/7956133.html

- Claire Wardle, “New report finds understanding differences in harmful information is critical to combatting it,” UN Peacekeeping, June 18, 2024, https://peacekeeping.un.org/en/new-report-finds-understanding-differences-harmful-information-is-critical-to-combatting-it

- Helen McElhinney, “What’s AI doing to information airways in conflict and crises?” CDAC Network, August 2024, https://www.cdacnetwork.org/news/whats-ai-doing-to-information-airways-in-conflict-and-crises

- Recorded Future Insikt Group, 2024 Annual Report: Cyber Threat Analysis, January 28, 2025.

- Raquel Vazquez Llorente, Ross Gildea, and Shirin Anlen, “Audiovisual generative AI and conflict resolution: trends, threats and mitigation strategies,” WITNESS, September 2024, https://www.gen-ai.witness.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/WITNESS-Report_Audiovisual_Generative_AI_and_Conflict-1.pdf

- Nick Robins-Early, “OpenAI says Russian and Israeli groups used its tools to spread disinformation,” The Guardian, May 30, 2024, https://www.theguardian.com/technology/article/2024/may/30/openai-disinformation-russia-israel-china-iran

- Volodymyr Solovian, “Artificial Intelligence in the Kremlin’s Information Warfare,” Ukraine Crisis Media Center, February 20, 2025, https://uacrisis.org/en/artificial-intelligence-in-the-kremlin-s-information-warfare

- Volodymyr Solovian and Matt Wickham, “The New Face of Deception: AI’s Role in the Kremlin’s Information Warfare,” Ukraine Analytica, no. 3 (35) (2024).

- Ina Fried, “Exclusive: Leading chatbots are spreading Russian propaganda,” Axios, June 18, 2024, https://www.axios.com/2024/06/18/ai-chatbots-russian-propaganda

- UN Human Rights Council, UN Doc. A/HRC/RES/55/10 (2024), April 5, 2024, para. 9.

- UN General Assembly, Pact for the Future, UN Doc. A/RES/79/1, September 2024.

- Mauro Fragale and Valentina Grilli, “Deepfake, Deep Trouble: The European AI Act and the Fight Against AI-Generated Misinformation,” Preliminary Reference Blog of the Columbia Journal of European Law, November 11, 2024, https://cjel.law.columbia.edu/preliminary-reference/2024/deepfake-deep-trouble-the-european-ai-act-and-the-fight-against-ai-generated-misinformation/

- “How the climate crisis is driving forced displacement in these five countries,” USA for UNHCR, August 29, 2024, https://www.unrefugees.org/news/how-the-climate-crisis-is-driving-forced-displacement-in-these-five-countries/

- Food Security Information Network (FSIN) and Global Network Against Food Crises (GNAFC), Global Report on Food Crises 2025, May 16, 2025.

- UNHCR, No Escape–On the frontlines of Climate Change, Conflict and Forced Displacement, November 2024.

- “Severe flooding compounds health crisis in South Sudan,” World Health Organization, October 21, 2024, https://www.afro.who.int/countries/south-sudan/news/severe-flooding-compounds-health-crisis-south-sudan

- Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC) and Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC), 2025 Global Report on Internal Displacement, May 13, 2025.

- IDMC, GRID 2025, May 2025, https://www.internal-displacement.org/global-report/grid2025/.

- IDMC and Notre Dame Global Adaptation Initiative Country Index (ND-GAIN). (2025). University of Notre Dame.

- IDMC, GRID 2025, May 2025, https://www.internal-displacement.org/global-report/grid2025/ “DR Congo: Deepening humanitarian catastrophe in Ituri completely forgotten,” NRC, March 28, 2024, https://www.nrc.no/news/2024/march/dr-congo-ituri-deepening-humanitarian-catastrophe “M23 conflict caused nearly 3 out of every 4 displacements in the DRC this year,” IDMC, September 23, 2024, https://www.internal-displacement.org/expert-analysis/m23-conflict-caused-nearly-3-out-of-every-4-displacements-in-the-drc-this-year/ Floodlist, Flooding in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Congo-Brazzaville, February 13, 2024; OCHA, République démocratique du Congo - Flash Update #2: De graves inondations affectent 18 provinces, February 7, 2024; IFRC, Floods in South Kivu and Tanganyika Provinces, May 2, 2024; “M23 conflict caused nearly 3 out of every 4 displacements in the DRC this year,” IDMC; “48.000 personnes déplacées aidées à Minova, prise au piège par les combats à l’est de la RDC,” Belgian Red Cross, June 13, 2024.

- IOM DTM, Yemen: Rapid Displacement Tracking Update, December 31, 2024; ACAPS, Yemen: Impacts of 2024 heavy rains, August 29, 2024 ; UNMHA, EO Incidents and Civilian Casualties in Hudaydah, August 2024.

- IDMC, GRID 2025, May 2025, https://www.internal-displacement.org/global-report/grid2025/

- Government of Nigeria/IOM, Joint Post-Flood Situation Report - Borno State, January 1, 2025.

- UN OCHA, Nigeria: Floods – Maiduguri (MMC) and Jere Floods Flash Update 1, September 10, 2024.

- ACAPS, Humanitarian impact of floods in Borno state, September 24, 2024; International Medical Corps, Nigeria Humanitarian Update: Situation Report #1, September 18, 2024; “Fears of outbreaks grow in Maiduguri following severe flooding,” MSF, September 20, 2024, https://www.msf.org/nigeria-fears-outbreaks-grow-maiduguri-following-severe-flooding Government of Nigeria/IOM, Joint Post-Flood Situation Report - Borno State; UNHCR, Protection Monitoring Report, August 22, 2024.

- CCCM, Shelter/NFI Sector, An update on camp closures in Borno State, July 9, 2024.

- UN OCHA, Nigeria: Floods – Maiduguri (MMC) and Jere Floods Flash Update 1, September 10, 2024.

- UN OCHA/UNICEF, Rapid Response Mechanism (RRM) Rapid Needs Assessment Report - Flood Response Muna IDP Camp, Jere (Dusman ward) Maiduguri, September 24, 2024.

- CCCM, Shelter/NFI Sector, An update on camp closures in Borno State.

- Ibid.

- ACAPS, Humanitarian impact of floods in Borno state, September 24, 2024.

- Government of Borno State, Strategy for Durable Solutions to Internal Displacement, June 2024.

- Ibid; Government of Nigeria, National Policy on Internally Displaced Persons, September 1, 2021.

- “With ‘Borno Model,’ Nigeria Hopes to Encourage Defections, Protect Civilians to Undermine Extremist Groups,” Africa Defense Forum, May 7, 2024; ICG, An Exit from Boko Haram? Assessing Nigeria’s Operation Safe Corridor, March 19, 2021; CCCPA, Advancing Holistic and Comprehensive Efforts to Confront Africa’s Growing Terrorism Challenge: A Nigerian Case Study on Developing Sustainable Pathways Out of Extremism for Individuals Formerly Associated with Boko Haram and ISWAP, June 2022; UN Peacebuilding, Strengthening reconciliation and reintegration pathways for persons associated with non-state armed groups, and communities of reintegration, including women and children, in Northeast of Nigeria, accessed September 2, 2025, https://www.unodc.org/conig/en/links/strengthening-reconciliation-and-reintegration-pathways-for-persons-associated-with-non-state-armed-groups--and-communities-of-reintegration--including-women-and-children--in-northeast-of-nigeria.html

- “We will stand behind you–UN assures, as States Action Plans for Durable Solutions in Northeast are launched,” UN Nigeria, May 28, 2024, https://nigeria.un.org/en/269846-we-will-stand-behind-you-un-assures-states-action-plans-durable-solutions-northeast-are Adamawa State Government, Adamawa State Homegrown Durable Solutions Action Plan for Internal Displacement, 2024; Yobe State Government, Yobe State Action Plan on Solutions to Internal Displacement, 2024.

- UNDCO, Coordinating Durable Solutions for Displacement in Nigeria, June 24, 2024.

- CIVIC and PAX, “Episode #8 (S2E2): Conflict, Climate, and the Environment, Part I: Ukraine,” Protection of Civilians Podcast, November 7, 2022.

- Benjamin Neimark, Frederick Otu-Larbi, Patrick Bigger, Linsey Cottrell, and Reuben Larbi, “A Multitemporal Snapshot of Greenhouse Gas Emissions from the Israel-Gaza Conflict [updated pre-print],” June 6, 2024.

- ICG, Fighting Climate Change in Somalia’s Conflict Zones, December 10, 2024.

- CIVIC, To Stem the Tide: Climate Change, UNMISS, and the Protection of Civilians, August 2024.

- Ibid.

- World Bank Group, Closing the gap: Trends in adaptation finance in fragile and conflict-affected settings, July 2024; UNHCR, No Escape–On the frontlines of Climate Change, Conflict and Forced Displacement, November 2024.

- “Top Line Messaging on the Climate Crisis for COP29,” Inter-Agency Standing Committee, November 8, 2024, https://interagencystandingcommittee.org/sites/default/files/2024-11/IASC%20Top%20Line%20Key%20Messaging%20on%20the%20Climate%20Crisis%20for%20COP29.pdf.

- G7+, The g7+ Joint Letter Calling for Urgent Action on Climate Financing – COP29, October 7, 2024.